Myanmar’s election under military rule faces widespread criticism as a ‘sham’, with fear, intimidation, and conflict overshadowing democracy efforts.

myanmar, election, military junta, aung san suu kyi, civil war, mandalay, democracy, USDP, nld, southeast asia

Myanmar’s Election: A Nation Gripped by Fear and Uncertainty

By Jonathan Head

South East Asia Correspondent, Mandalay, Myanmar

On the dusty banks near the Irrawaddy River, retired Lieutenant-General Tayza Kyaw, now an aspiring member of parliament, strives to rouse a weary crowd with promises of better times. As the Myanmar’s election looms, he represents the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), staunchly backed by the military in Mandalay’s Aungmyaythazan constituency. The crowd, mainly families affected by a recent earthquake, gathers in hope for a handout but quickly disperses once the rally concludes.

A ‘Sham’ Election: Democracy Under Siege

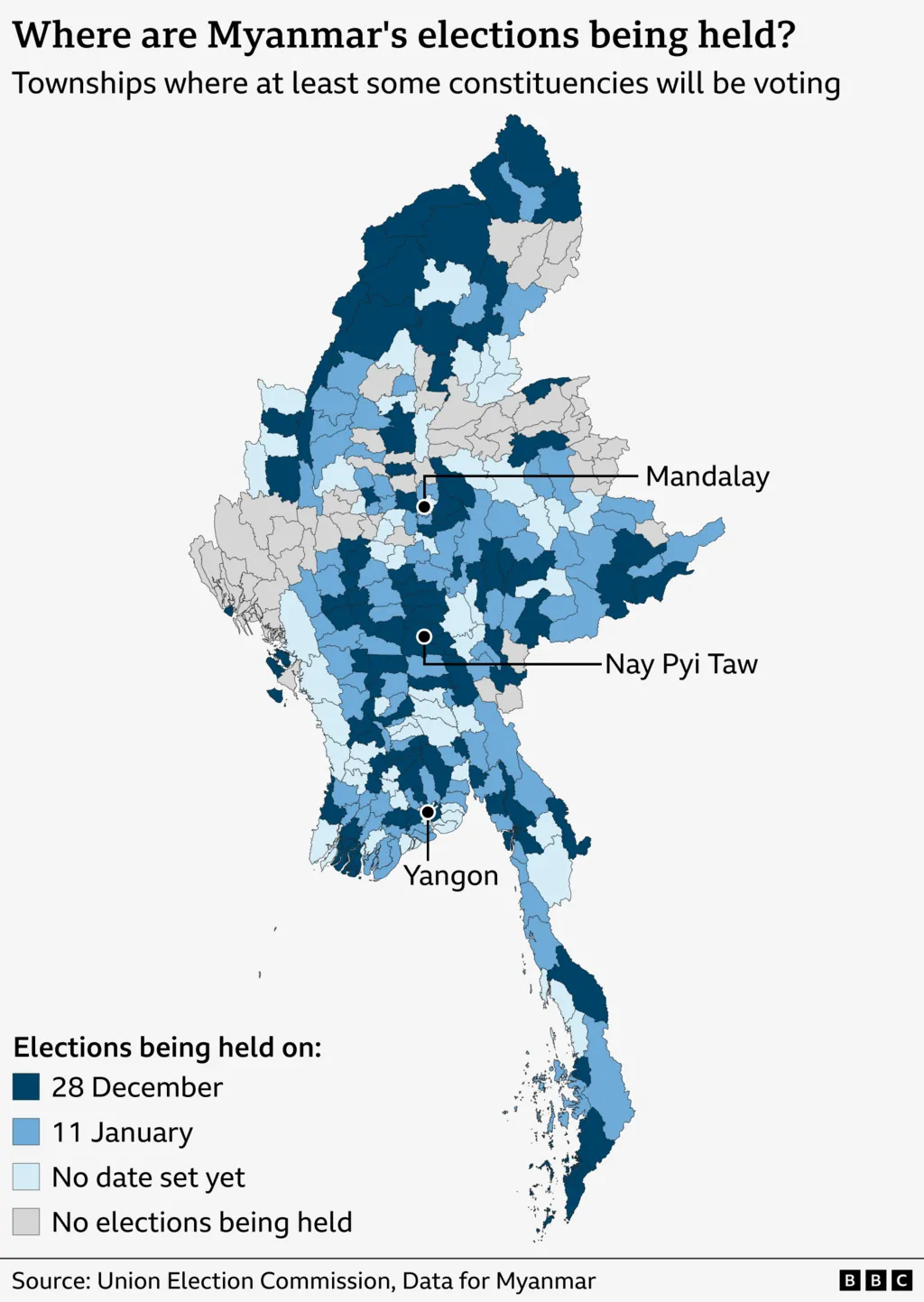

This Sunday, the people of Myanmar are afforded their first chance to vote since the military coup nearly five years ago triggered a devastating civil war. Despite repeated postponements, the poll is widely dismissed as a sham: the National League for Democracy (NLD), the most popular party, has been dissolved and its leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, remains imprisoned in a secret location.

Voting will occur in three stages over a month, but conflicts will prevent large swathes of the country from participating. Even areas holding ballots are beset by fear with government agents monitoring conversations and activists wary of dire consequences for dissent. For an in-depth overview of Myanmar’s political turmoil, see the Encyclopædia Britannica entry on Myanmar.

Fear and Intimidation: Silencing Dissent

Attempts to gauge public opinion at rallies are quickly suppressed by party officials and a tangible sense of anxiety prevails. Even the act of expressing skepticism or liking critical content on social media has been criminalized. This hostile environment is palpable on the streets—people fear answering questions, wary of government retaliation.

“This election is a lie. Everyone is afraid. Everyone has lost their humanity and their freedom. So many people have died, been tortured or fled to other countries. If the military keeps running the country, how can things change?”

Many opt out of voting altogether, despite knowing such decisions are fraught with personal danger.

Legal Crackdowns and Harsh Penalties

In July, authorities introduced sweeping laws banning speech or protest that could “destroy a part of the electoral process.” High-profile activists like Dr. Tayzar San have been charged for distributing boycott leaflets, with rewards offered for their arrest. In Yangon, three young people were sentenced to decades in prison for simple protest stickers. The climate of intimidation is deliberate and pervasive.

Public spaces are filled with propaganda. A large red poster in Mandalay commands citizens to “co-operate and crush all those harming the union,” underscoring the menacing atmosphere ahead of Myanmar’s election.

A General’s Gambit: The Junta’s Bid for Legitimacy

Despite the chaos, junta leader Min Aung Hlaing appears optimistic. He believes these elections—even though polling will not occur in half the nation—will confer the legitimacy he desperately craves. In a symbolic gesture, Min Aung Hlaing attended Christmas Mass in Yangon, decrying hatred and violence. Yet he faces international charges for genocide against the Rohingya and is blamed for a civil war estimated by ACLED to have killed nearly 90,000 people.

External Influences and Election Outcomes

China, despite its one-party system, is lending technical and financial support in a bid to ease the deadlock caused by the coup. Set to be grudgingly accepted by other Asian nations, the election offers an exit strategy for the junta, especially now that the NLD is barred from competing.

Armed with new Russian and Chinese weapons, the military is reclaiming lost ground, aiming to expand voting to more regions in later stages. With the NLD removed, the USDP is virtually guaranteed victory, marking a sharp contrast from the 2020 vote when it only secured six percent of parliamentary seats.

However, even within the regime, Min Aung Hlaing’s leadership is contested. Should he retain power, it will likely be with diminished influence, as parliamentary politics resume—albeit without much true opposition.

Life Amid Conflict: No Compromise in Myanmar

Just outside Mandalay, the impact of civil war is unmistakable. The journey to the temple complex at Mingun—once a tourist hub—is now fraught with danger, as both government forces and People’s Defence Forces (PDFs) control contested zones. Traveling the region requires negotiating with armed local police and passing through numerous checkpoints.

Village police, often young and visibly strained, describe a life of constant threat. Various armed groups—like the Unicorn Guerrilla Force—refuse negotiation, and gunfire marks the limits of engagement. Elections will not reach many northern villages, as both sides of the conflict refuse to compromise.

Disillusionment and Defiance

The military remains unrepentant, blaming resistance groups for civilian casualties. General Tayza Kyaw firmly labels the opposition as “terrorists,” absolving the military of responsibility for the mounting toll.

The energy and hope of the 2020 election are all but absent. Only five minor parties are permitted to challenge the USDP nationwide, and none hold significant resources. As the public is worn out by violence and repression, voter turnout is expected to be low.

“We will vote,” one woman said, “but not with our hearts.”

Additional reporting by Lulu Luo

Learn More About Myanmar’s Political History

Source: Original BBC report